Windows 8.1 radically changes the address space layout of the system by finally removing the 44-bit limitation which I described in one of the earliest blog posts on this website (and which Wikipedia even links to!). This is a little-known detail about the operating system, and an odd thing for Microsoft not to emphasize on with more aplomb, especially given that 8.1 is considered a “patch” of Windows 8.

Now, you may think that 16 TB to 256 TB is a meaningless change since no applications currently use even a fraction of that space, but the main benefit of this change are not the ability to allocate additional memory, but rather the increased entropy space available for Address Space Load Randomization (ASLR), especially given that Windows 8 introduced High Entropy ASLR (HEASLR), Top-down Randomization and Anonymous Memory Randomization.

Additionally, another key change was done in Windows 8.1 that is not mentioned anywhere. As Pavel Lebedinsky, one of the lead SDETs on the Memory Manager and an extremely helpful individual indicated on one of the blog posts from Mark Russinovich:

1. Reserved memory does contribute to commit charge, because the memory manager charges commit for pagetable space necessary to map the entire reserved range. On 64 bit this can be a significant number (reserving 1 TB of memory will consume approximately 2 GB of commit).

This means that attempting to reserve the full 8 TB of memory on Windows 7 results in 16 GB of commit, which is beyond’s most people’s commit limit, especially at the time. In Windows 8.1, this would result in 128 GB of commit being used, which only a beefy server would tolerate. While such large memory reservations are unusual, they do have usefulness in certain scenarios related to security and low-level testing. This Windows behavior prevented such reservations from reliably working, but in Windows 8.1, the limitation has been removed!

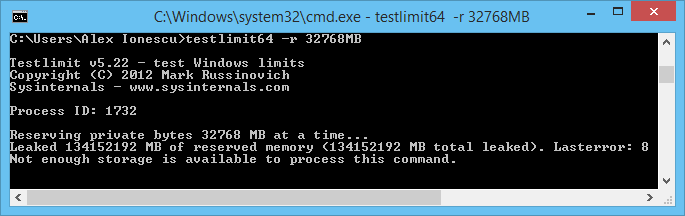

Indeed, you can easily test this by using the TestLimit tool from the Windows Internals Book, and run it with the -r option (and preferably with a large enough block size). Here’s a screenshot of hitting the 128 TB reservation:

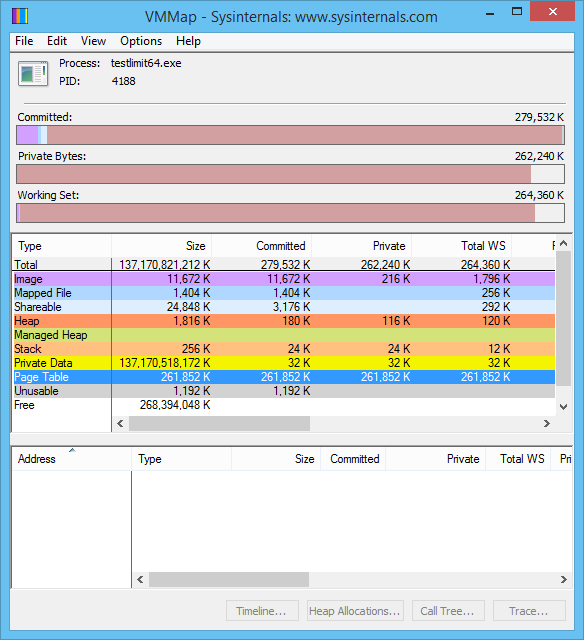

And here’s the resulting view in VMMap, which does not show the expected page table commit charge, but rather a much smaller size (256 MB).

So why did Microsoft change this behavior in Windows 8.1? Well, Windows 10, as well as Windows 8.1 Update 3 (November Update) make this clear. As I previously tweeted, these OS versions enable Control Flow Guard (CFG), a feature that laid dormant in the first versions of Windows 8.1. In order to function, CFG requires the use of optimized bitmaps in order to determine the validity of indirect calls, and on 64-bit Windows, this bitmap requires 2 TB of space. Not only would this cut the Windows 8 address space by 25%, it would’ve also resulted in 4 GB of per-process commit!

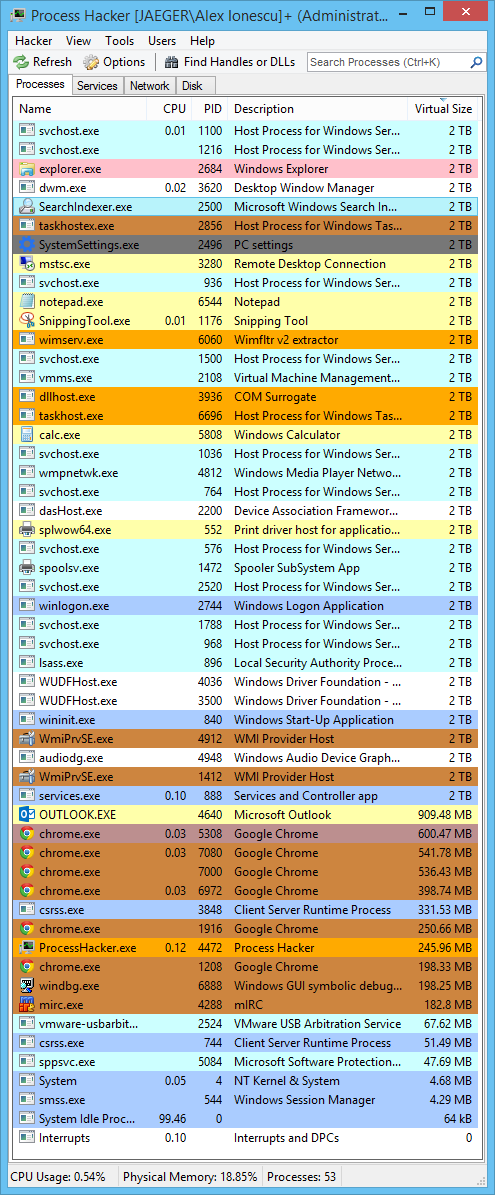

Here’s a screenshot of Process Hacker showing how all CFG-enabled processes now use 2 TB of virtual address space:

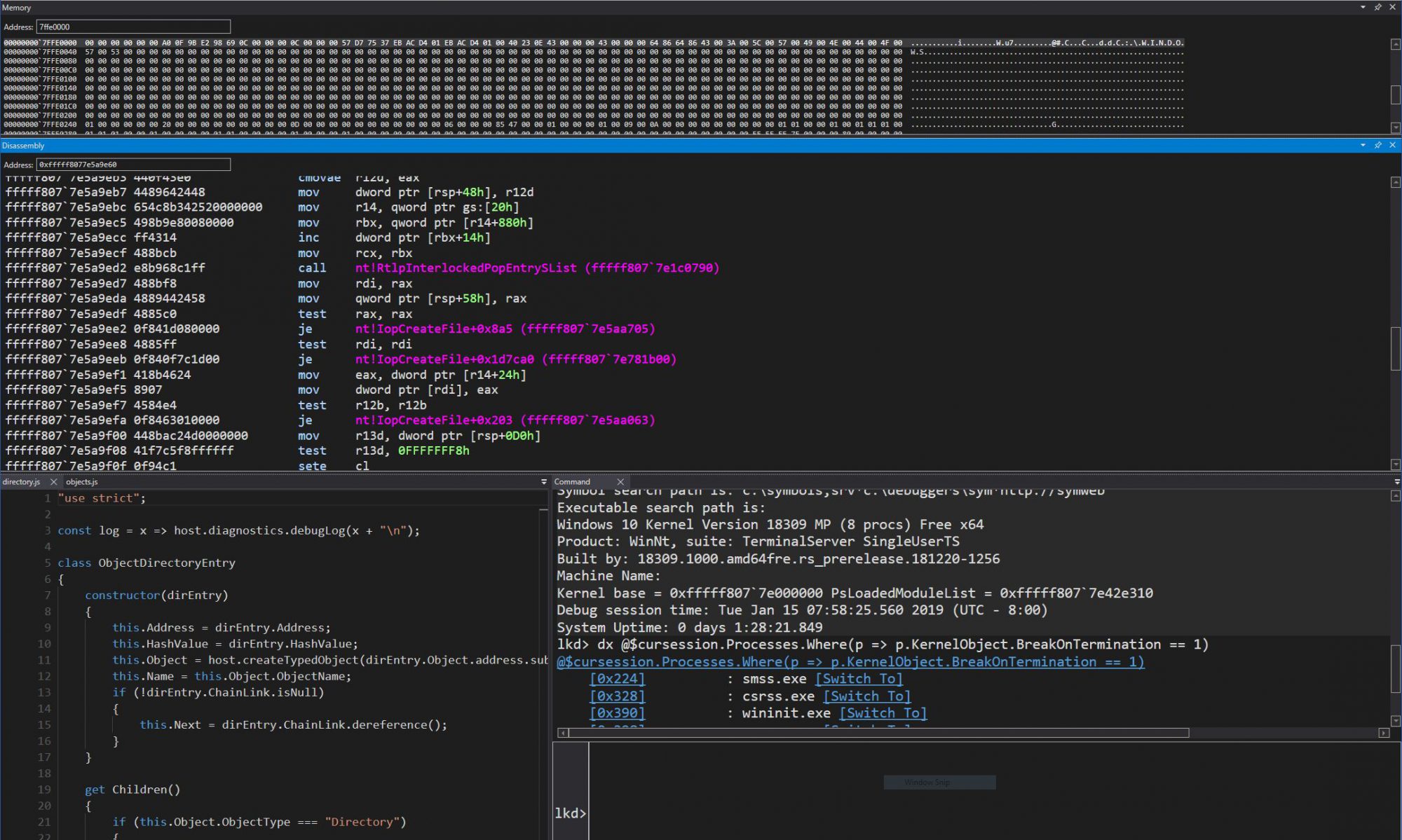

The final effect of this change from 8 TB to 128 TB is that the kernel address space layout has significantly changed. And sadly, the !address extension in WinDBG is broken and continues to show the Windows 8 address space layout (which I expanded on during my Blackhat 2013 talk), while the Windows Internals book is stuck on Windows 7 and doesn’t even cover Windows 8 or higher.

Therefore, I publish below what I believe to be the only public source of information on the Windows 8.1 x64 memory layout. One of the benefits of this new layout is that it now becomes extremely easy by using the first 5 or 6 nibbles of an address to determine where it’s coming from. For example, 0xFFFFD… is a kernel stack, 0xFFFFC… is paged pool, 0xFFFFF8… is a loaded image (driver or kernel), and 0xFFFFE… is nonpaged pool.

| Start | End | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFFF0000`00000000 | FFFF07FF`FFFFFFFF | 8TB | Memory Hole |

| FFFF0800`00000000 | FFFFAFFF`FFFFFFFF | 168TB | Unused Space |

| FFFFB000`00000000 | FFFFBFFF`FFFFFFFF | 16TB | System Cache |

| FFFFC000`00000000 | FFFFCFFF`FFFFFFFF | 16TB | Paged Pool |

| FFFFD000`00000000 | FFFFDFFF`FFFFFFFF | 16TB | System PTEs |

| FFFFE000`00000000 | FFFFEFFF`FFFFFFFF | 16TB | Nonpaged Pool |

| FFFFF000`00000000 | FFFFF67F`FFFFFFFF | 6.5TB | Unused Space |

| FFFFF680`00000000 | FFFFF6FF`FFFFFFFF | 512GB | PTE Space |

| FFFFF700`00000000 | FFFFF77F`FFFFFFFF | 512GB | HyperSpace |

| FFFFF780`00000000 | FFFFF780`00000FFF | 4K | Shared User Data |

| FFFFF780`00001000 | FFFFF780`BFFFFFFF | ~3GB | System PTE WS |

| FFFFF780`C0000000 | FFFFF780`FFFFFFFF | 1GB | WS Hash Table |

| FFFFF781`00000000 | FFFFF791`3FFFFFFF | 65GB | Paged Pool WS |

| FFFFF791`40000000 | FFFFF799`3FFFFFFF | 32GB | WS Hash Table |

| FFFFF799`40000000 | FFFFF7A9`7FFFFFFF | 65GB | System Cache WS |

| FFFFF7A9`80000000 | FFFFF7B1`7FFFFFFF | 32GB | WS Hash Table |

| FFFFF7B1`80000000 | FFFFF7FF`FFFFFFFF | 314GB | Unused Space |

| FFFFF800`00000000 | FFFFF8FF`FFFFFFFF | 1TB | System View PTEs |

| FFFFF900`00000000 | FFFFF97F`FFFFFFFF | 512GB | Session Space |

| FFFFF980`00000000 | FFFFFA70`FFFFFFFF | 1TB | Dynamic VA Space |

| FFFFFA80`00000000 | FFFFFAFF`FFFFFFFF | 512GB | PFN Database |

| FFFFFFFF`FFC00000 | FFFFFFFF`FFFFFFFF | 4MB | HAL Heap |

One Reply to “How Control Flow Guard Drastically Caused Windows 8.1 Address Space and Behavior Changes”